2022

AFTER FUTUROLOGY

"More than one still expects something from the future". Ossip K FLECHTHEIM, Ist die Zukunft noch zu retten?, 1987 "Was it the dear old future that created the problems we face?" Neil TENNANT, This used to be the Future, 2008 2022 is the name of the project that Christto & Andrew (Christto Sanz, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1985 and Andrew Weir, Johannesburg, South Africa, 1987) will present on 10 June 2022 at House of Chappaz. Probably by the time you read this, this future will also be the past. To inhabit the gap between the past and the future implies constructing our existence in a historical present projected from past events. This discourse also configures aesthetic and imaginary apparatuses that are no less reflections of the moment in which they were conceived. From these, the pair of artists reinterpret these imaginaries in new images, a nostalgic approach to other futures centred on the sixties and eighties of the last century. Flechtheim, who had coined the term futurology two years earlier, published Teaching the Future in 1945, and when reviewing his own work two decades later he already pointed out that technical advances made it possible to establish a high "degree of credibility and probability of forecasts". In 1960, the future ceased to be something hypothetical and became established as a computable historical period, although the anticipatory gaze, which had previously been directed at centuries and millennia, was shortened to concentrate on the coming decades. The sixties thus mark a transformation in the vision of the future, shortening its durability while at the same time shaping its verisimilitude. The eighties brought a new change, the crisis of the Euromissiles standardised an apocalyptic future based on self-extermination. So it is not strange that, from today, these decades and their aesthetic imaginaries configure the turning points in the perception of the future that artists have wanted to emphasise. "But even more so, when a photograph was taken, the photographer, on the one hand, and above all the object apprehended, on the other, "knew" that they were working for the future. They were not unaware that they were addressing a stranger from the future, from whom they are asking a simple but imperative thing, which belongs to the order of duty and therefore to the law: to name them." Jean-Louis Déotte, What is an aesthetic apparatus? Benjarmin, Lyotard, Ranciére, 2007. It is not by chance that in order to project this past of the future, Christto & Andrew turn to photography. Since its birth as a technology for capturing the present, the photographic image has been shaping our futures. If, as Jameson (2007) points out, our archaeologies of the future are constructed as a chimera, anchored in our systems of production, technological imaginaries are also aspects of this construct that we project. Both the form and the substance of the 2022 project are fed by these ruins of the future that are evidence of our experiences and desires. As in the sixties, our projection has been shortened, as in the eighties, the forecasts are increasingly catastrophic. It may be that, just as it began with the modern era, the idea of the future is over. "If the past and the future did not become part of the present through memory and intention, there was, in human terms, no way, nowhere to go." Ursula K. LE GUIN, The Dispossessed, 1974 The world has already ended so many times, at least in the West. The Christian calendar has placed the end in the year 1000, 1836, 1844 or 2000. Scientists have given us a little more time, such as Meadows who points to 2050 as the limit of civilisation's growth. The truth is that in almost all scenarios we are still living in borrowed time. Even when we conceive of historical time in a cyclical way, we are still struck by how events between the so-called First and Second World Wars repeat themselves as if they were a script to be followed. Lucian Hölscher, in The Discovery of the Future, 1999, defines it as an invention, stating that "the ability to project into the future is not an anthropological constant, (...) but a historically specific way of thinking". It may be this historical notion that has excluded many collectives from thinking, and projecting, into the future. "This way of seeing and thinking can lead to the emergence of a symbolic ideography." Aby WARBURG, The Ritual of the Serpent, 1923 If we take No to the Future. Queer theory and the death drive by Lee Edelman, 2004, as an example of the fact that there is no imaginary and it is necessary to construct utopias, and the words of Derek Jarman, in which he stated that he lived within a collective without history and, therefore, without a past, there are many of us who are only allowed to live in the present. Individuals who inhabit the block universe enunciated by Broad can at least inhabit a present with a past but without a future. Yet we have accepted the existence of other possible worlds, even though Fermi has already pointed out this paradox, embracing a memory of the future and welcoming with nostalgia those days we hope will come. In the meantime, as so often, the world has ended and we can only contemplate some remains, colourful photographs, of what we expected of it. Text by Eduardo García Nieto, Independent curator and educator Photos by Nacho López Ortiz

Available works

Age of Aquarius Christto & Andrew

Photography 100 x 70 cm Ed. 1/5 + 2 AP

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: 2022

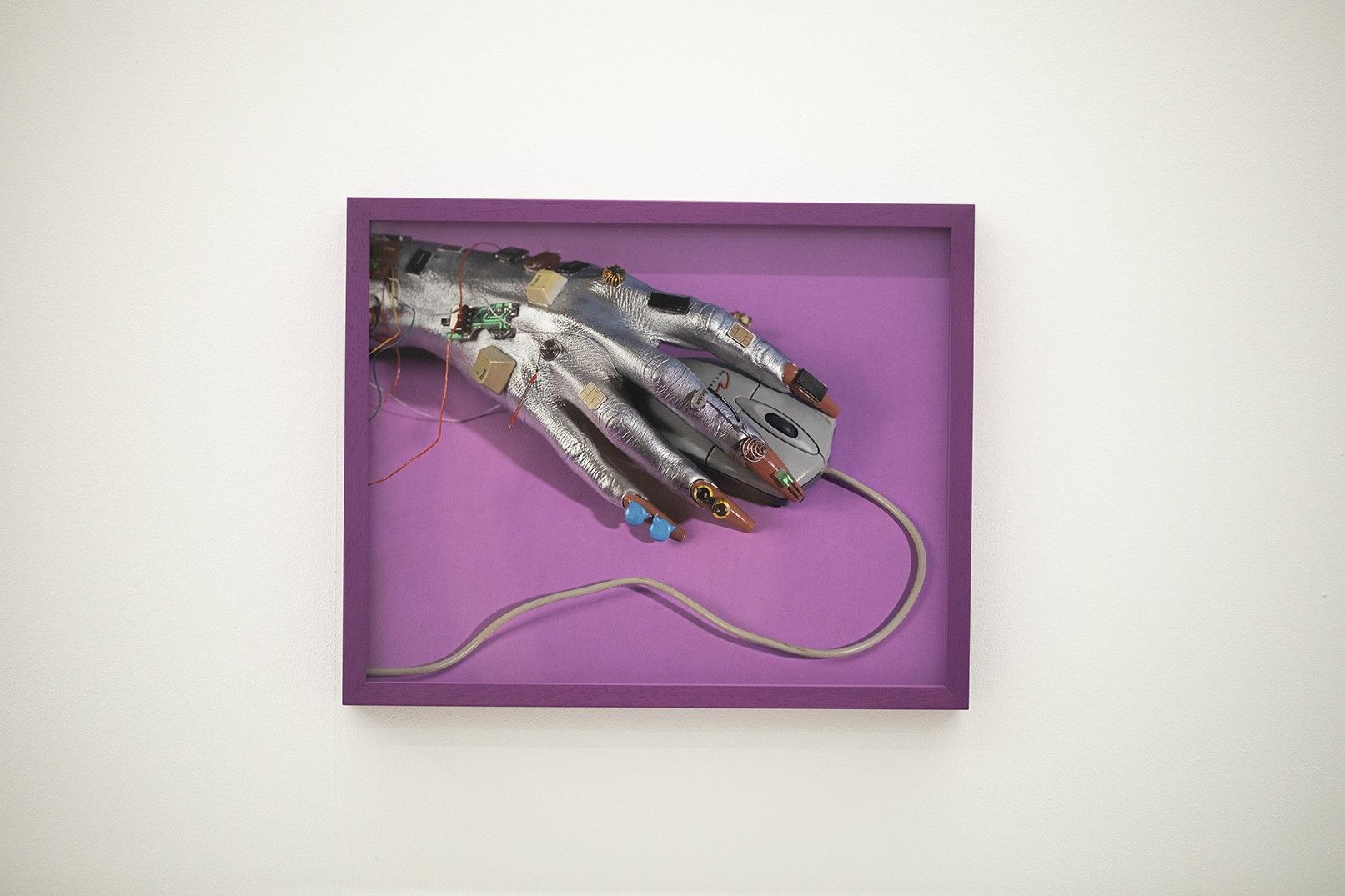

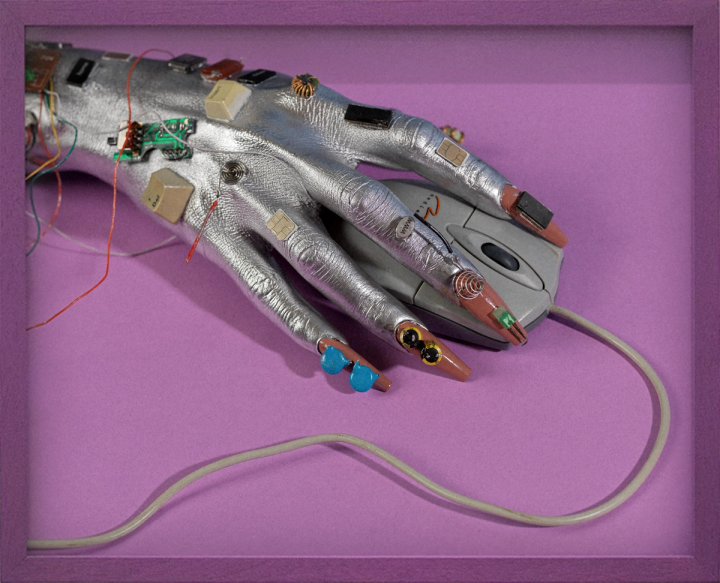

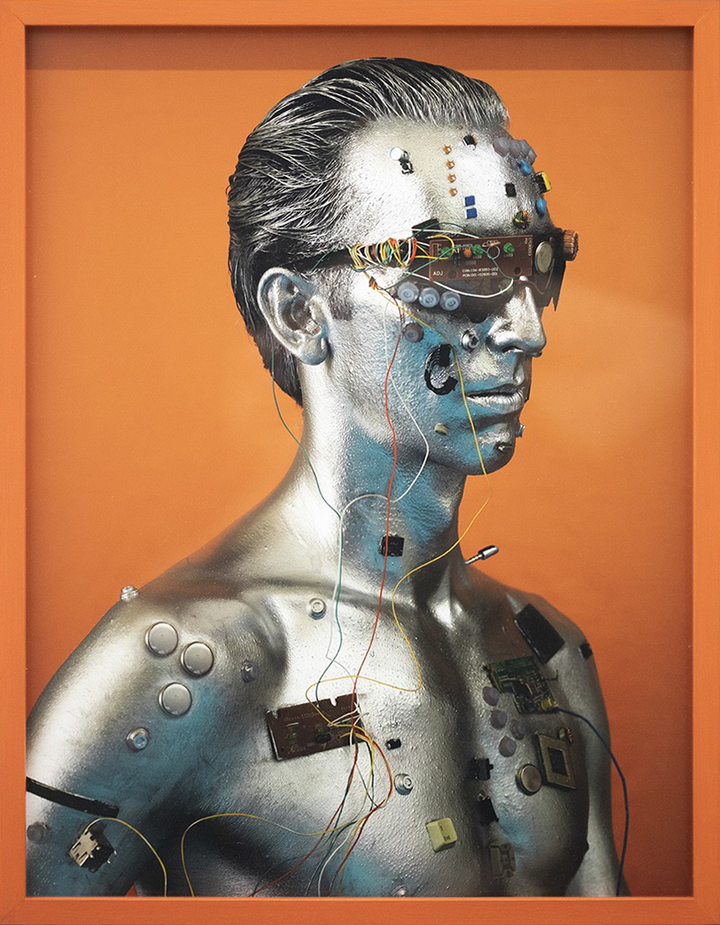

#A.I touch_ Christto & Andrew

Epoxy resin, false nails, and wiring with internal circuitry Dimensions vary Unique piece

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: W.O.R.M. / 2022 2022

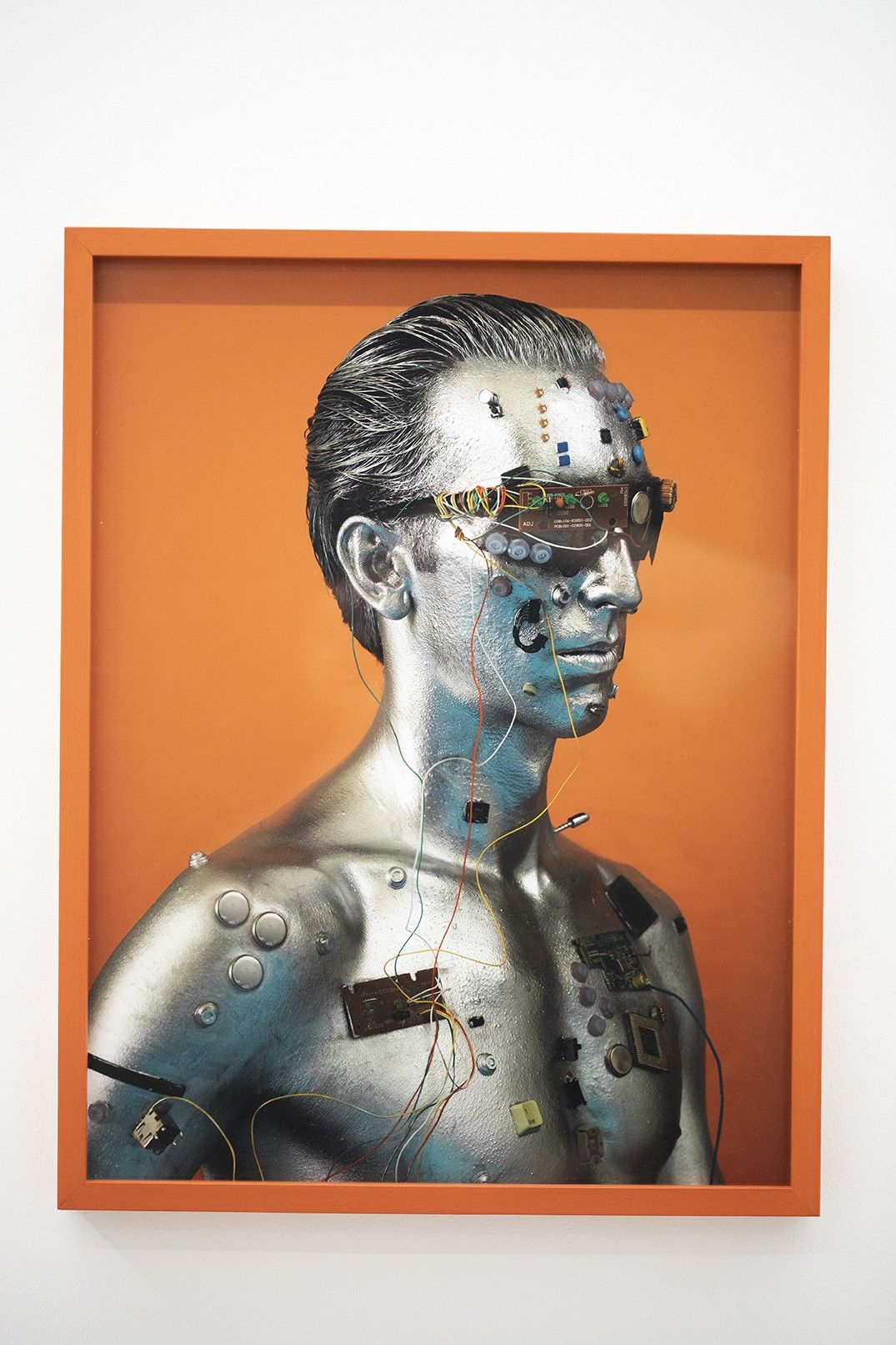

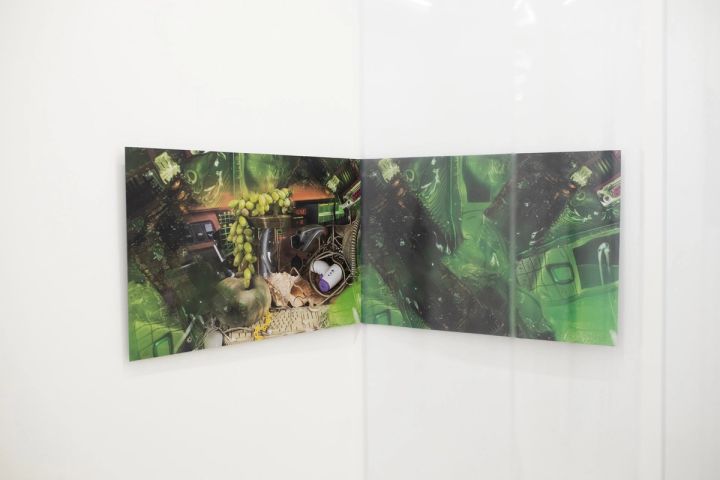

A Sci-Fi Movie From the Past Christto & Andrew

Photography 40 × 50 cm Ed. 1/5 + 2 AP

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: W.O.R.M. / 2022 2022

Memory of a Machine with Exabytes of Data Christto & Andrew

Photographic installation 90 x 60 cm (x2) Ed. 1/3 + 2 AP

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: W.O.R.M. / 2022 2022

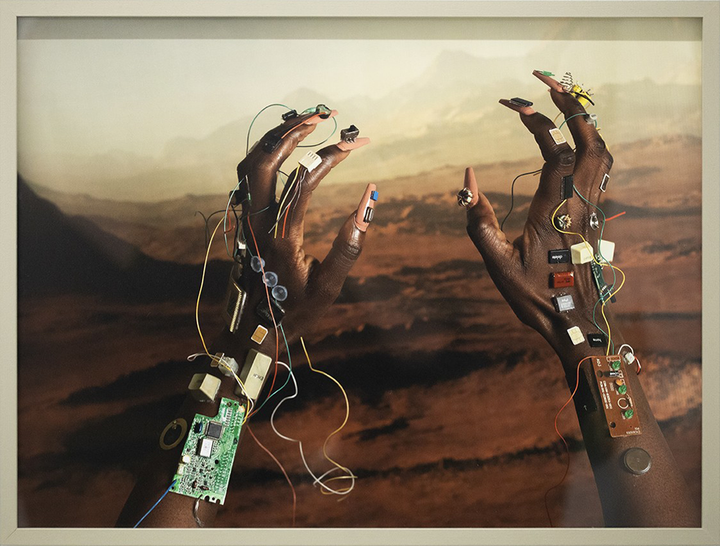

Prophetic Abilities of the Future Christto & Andrew

Photograph 80 x 60 cm Ed. 1/5 + 2 AP

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: W.O.R.M. / 2022 2022

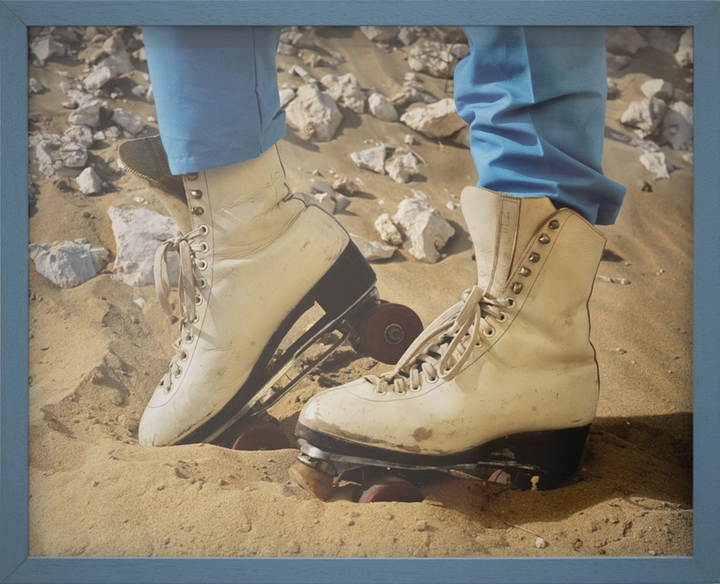

Stuck in the Desert Hack Christto & Andrew

Photograph 50 x 40 cm Ed. 1/5 + 2 AP This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: W.O.R.M. / 2022 2022

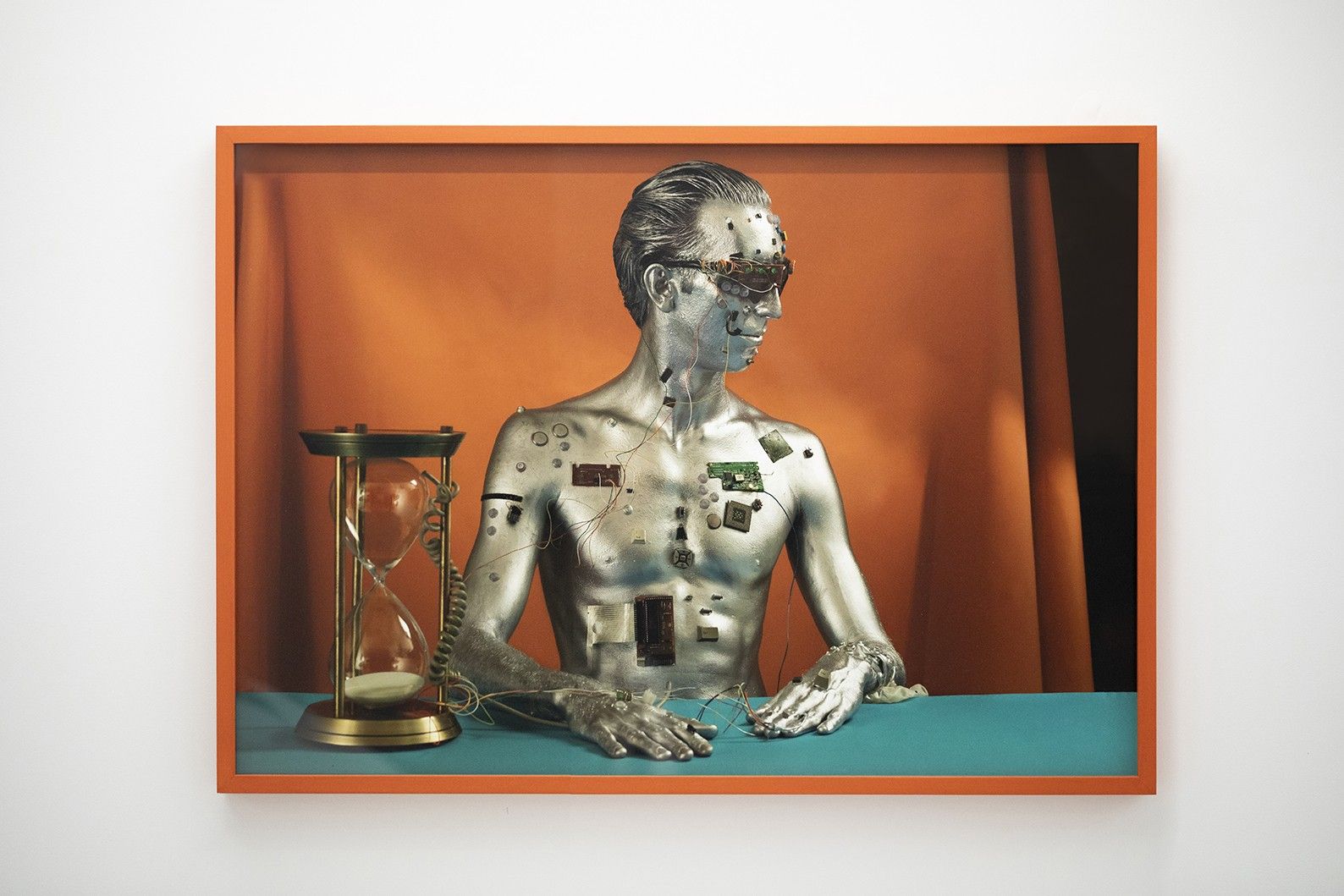

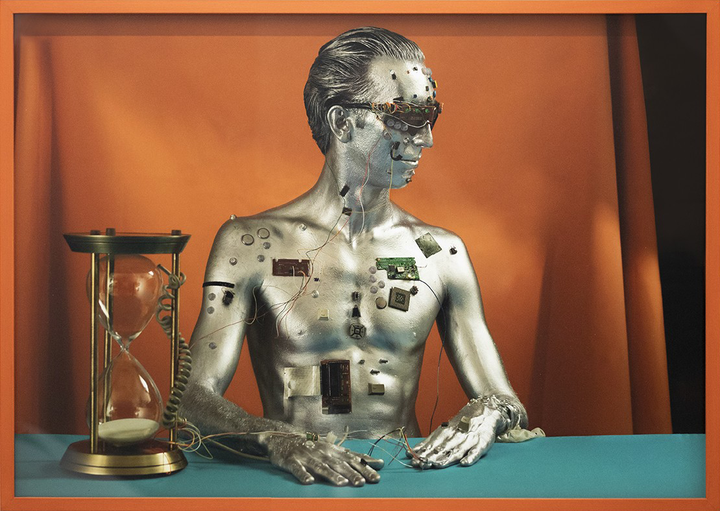

The Future Ain't What is Used to be (The Serpent that Gives Us Knowledge) Christto & Andrew

Photograph 100 × 140 cm Ed. 1/3 + 2 AP

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: 2022

Trapped in Time Christto & Andrew

HD Video 5 minutes Ed. 1/3 + 2 AP

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: W.O.R.M. / 2022 2022

Welcome to 2022 Christto & Andrew

Photography 50 x 65 cm Ed. 1/5 + 2 AP

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: W.O.R.M. / 2022 2022

Related exhibitions

This Fucking Name Christto & Andrew,Andrew Roberts,Aggtelek,Diego del Pozo Barriuso,Fito Conesa,Momu & No Es,Natacha Lesueur,Ovidi Benet,Pablo Durango

From March 11 to June 30, 2022

W.O.R.M. / 2022 Christto & Andrew,Sarah & Charles

From March 21 to May 16, 2025