Las Novias de Frankenstein

The fifth photo

“'How dare you,' says the angel. He crashes down from the heights”PJ Harvey, Pig Will Not, 2009 One of the aspects that characterized the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889 was the technical development, exemplified not only by the construction of the Eiffel Tower, but also by the Machine Gallery in which, probably, one of the Belgian inventions that transformed infant mortality rates: the incubator. I do not know the impact of this novelty, probably buried among a myriad of technical wonders, but the one who did notice it was Alice Guy, or at least that anecdote is pointed out as the germ of The Cabbage Fairy, 1896, considered not only the first film directed by a woman, or at least signed by one, and the first narrative film. The fairies will be present at the beginning and in the history of cinema, but they will be basic to understand the development of the photographic image, both static and in movement, but they will accompany us to Cottingley, England, where in the summer of 1917 some girls Elsie Wright , aged sixteen, and Frances Griffith, aged ten, took two snapshots in which they could be seen surrounded by fairies. At least that is what the protagonists of the five photographs that showed them portrayed with these creatures affirmed, in all but the fifth and last of the images. The news generated a major stir, with numerous scholars insisting on its veracity and with Conan Doyle echoing the discovery. Kodak refused to authenticate them, saying there were many ways to counterfeit them. In 1981 these women affirmed that this was the case, that they had falsified the photographs, all except the fifth. While the dada was exploring the expressive possibilities of photomontage, devised half a century earlier, some young cousins were using it, generating a verisimilitude fiction and remaining silent, ashamed for having managed to deceive the creator of Sherlock Holmes. The first image shows Frances looking at the camera, the following ones offer us the profiles of the protagonists, since they are interacting with the fairies, translucent entities that further emphasize the Camp fantasy that builds these images and that is still a reflection of education and the universe of a “feminine” childhood. 1935, James Whale premieres the sequel to Frankenstein, generating a new character that did not exist in Mary Shelley's fiction, the creature's girlfriend. The story picks up where it had ended, in the ruins of the mill, and the creature begins a pilgrimage in search of people who accept him as he is. One of the most important aspects is the criminalization through the gaze, if in Shelly's novel the creature discovers its monstrous nature when reading Milton's Paradise Lost, in the film it is the gaze of others that reminds it of its inadequacy to the pattern, placing it in the field of the abject. If in the first film the exception to this social dynamic was found in the girl, in this second part it will be the blind man who accepts the being. The Bride of Frankenstein, which is the title of the film, is a longing that is instilled in the character, of the same nature that the creature is frightened when looking at him for the first time, which causes him to flee and die. The role of this girlfriend, like that of Duchamp, is passive, her goal is to please male desire, in this case affection and companionship, but she breaks the pattern, rejecting her 'fiancé' despite sharing the same 'monstrous nature'. It is seeing herself reflected in another that leads her to fear or the weariness of being modeled and manipulated by the male gaze to meet her expectations and by refusing she breaks the pattern. The truth is that the female version of the creature is once again a patchwork of elements that seek to adapt it to an ideal. And within the visual construction of that bride we cannot forget her hair... “Almost everything that has been written on the subject agrees that clothing serves three main purposes: adornment, modesty, and protection. (…) Most researchers have unhesitatingly considered adornment as the motive that led to the adoption of dress. (…) Anthropological data is based on the fact that among the most primitive races there are peoples who do not dress, but not peoples who do not adorn themselves.” J.C FLÜGEL, Psychology of clothing, 1935 Natacha Lesuer (Cannes, 1971) presents her second solo show in Valencia, The Brides of Frankenstein, after her retrospective at the Villa Medicci, Rome. The title of the project already takes us into some of her obsessions: the notion of femininity as a construct, the supposed alterity of ornament, the topics and modes of representation put in crisis by feminist thought... The exhibition presents his latest series, Les humeurs des fées, 2020-21, in dialogue with previous works, the oldest being from 1997. Organized around series, his production develops an exploration of identity and the body in the that the construction of the image prevailed before the rest of the elements, almost all these works are “Untitled” compared to this last proposal. The vision of the feminine as a fiction, in this case through the mythology of fairies, in which the image is assaulted by the abject in the most Freudian sense of the term: fluids, rot, fires... We have already pointed out how the fairies, and the aesthetic keys that would cement the camp, were found as a leitmotif among the initiators of photography and cinema. But the other tradition would link us with artists like Dürer. According to Greek medical philosophy, people would be built on the basis of four fluids or humors: phlegm, blood, black bile, and yellow bile. These fluids affected both our physical and mental health and moods -Les humeurs, in French, while in Spanish the term designates only one emotional aspect. The excess of black bile was linked to melancholy and artistic characters, prone to hearing problems, that's why they cover their ear with their hand. The women portrayed by Natacha find themselves trapped in a melancholic universe, in which the symptoms contaminate the perfection of the image, evidencing the underlying disease, caused by the expectations towards women in contemporary society. Perhaps the horror felt by the bride of Frankenstein when confronted with her monstrosity is the reflection caught in our own eyes as we contemplate what we are doing to ourselves. Text by Eduardo García Nieto, Independent curator and educator Photos by Nacho López Ortiz

Available works

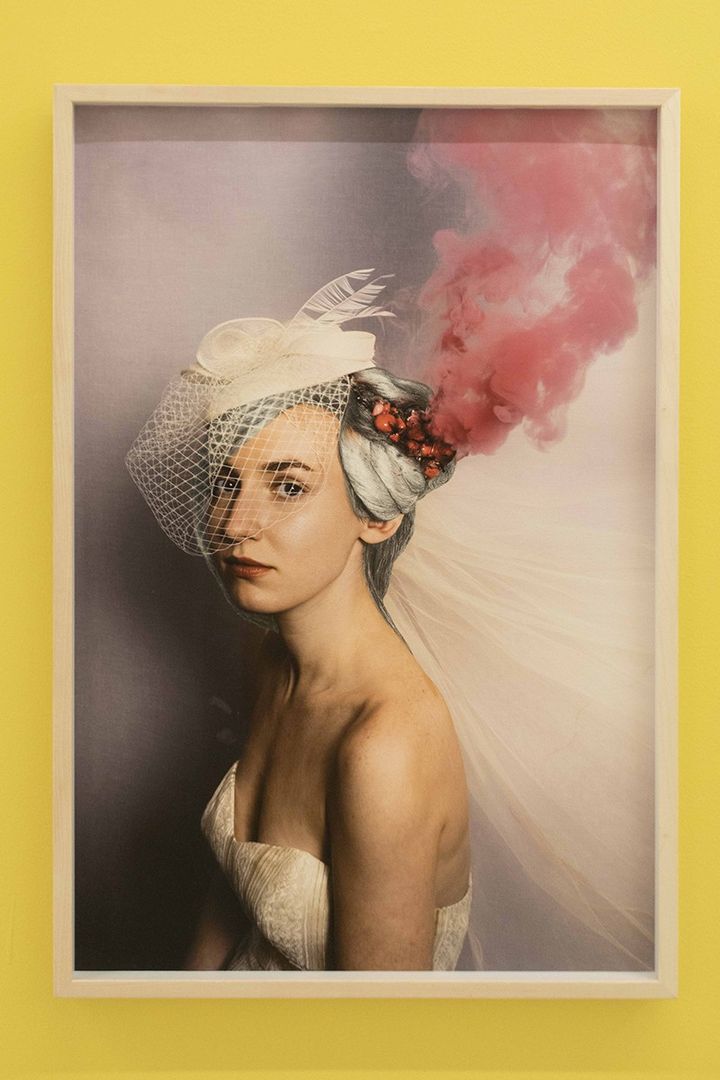

Foyer de Fée Natacha Lesueur

Graphite mine monotype in print Fine Art Pigment Photography Signed, dated and justified on the back 1/3 115 x 76 cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

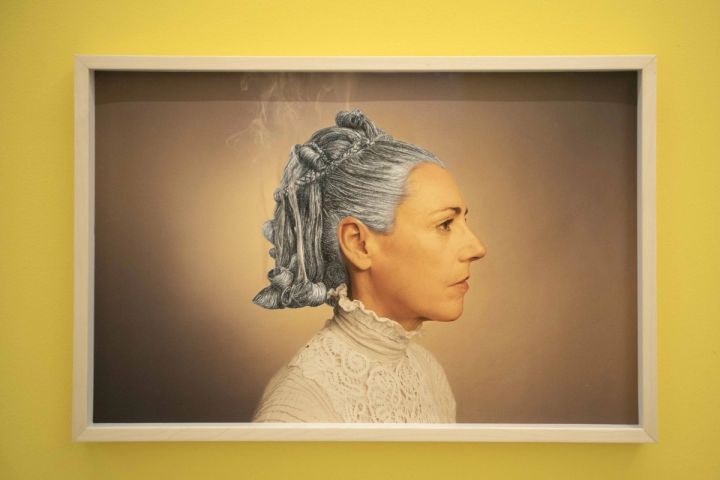

S/T Natacha Lesueur

Graphite mine monotype in print Fine Art pigment photography 100 x 100 cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

S/T Natacha Lesueur

Graphite mine monotype in print Fine Art pigment photography 110 x 110 cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

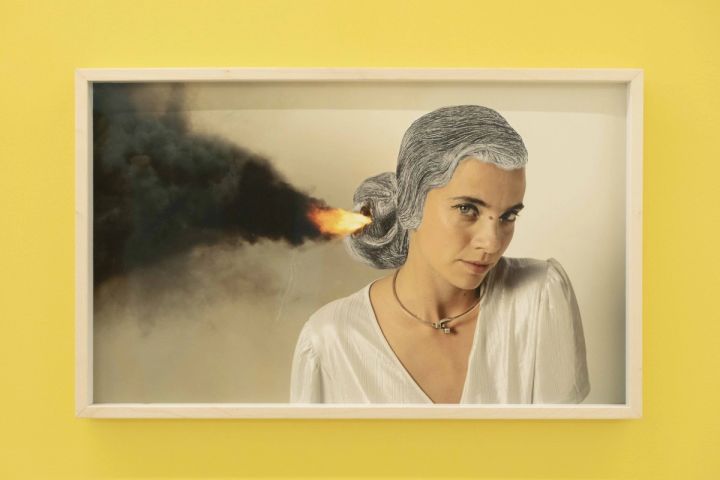

S/T Natacha Lesueur

Graphite mine monotype in print Fine Art pigment photography 94 x 109 cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

S/T Natacha Lesueur

Graphite mine monotype in print Fine Art pigment photography 94 x 109 cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

Fée Cerise Natacha Lesueur

Graphite mine monotype in print Fine Art pigment photography Signed, dated and justified on the back 1/3 74.5 x 49.5 cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

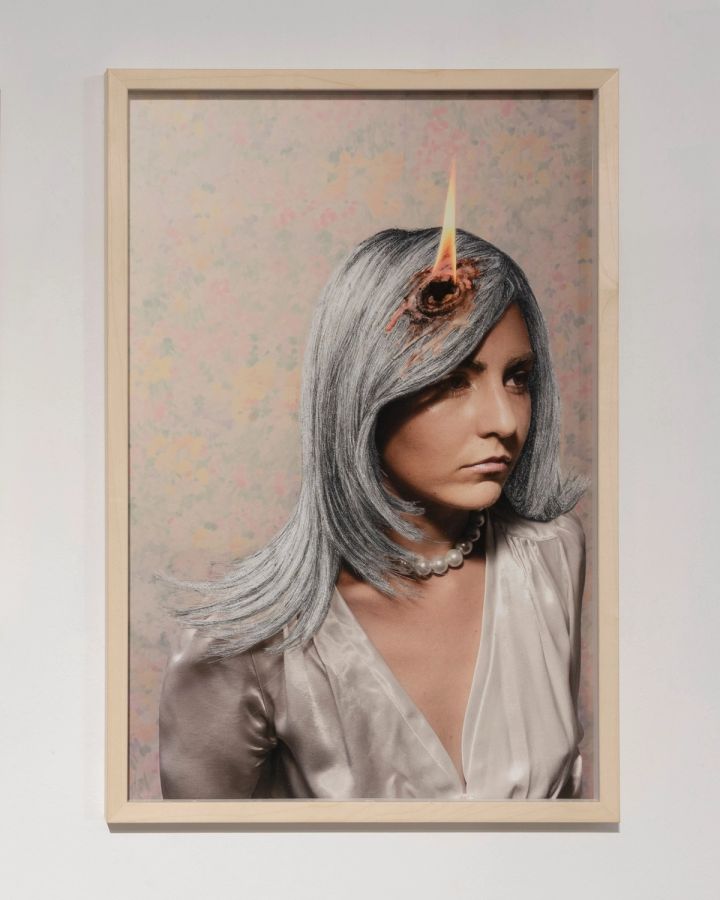

Archi Fée Natacha Lesueur

Graphite mine monotype in print Fine Art pigment photography Signed, dated and justified on the back 1/3 42 x 62 cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

Fée Couronne Natacha Lesueur

Graphite mine monotype in print Fine Art pigment photography Signed, dated and justified on the back 1/3 48x48cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

Fée du Logis Natacha Lesueur

Graphite lead monotype in print Fine Art pigment photography Signed, dated and justified on the back 1/3 40 x 50 cm and 55 x 37 cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Mixtape Vol1 Las Novias de Frankenstein

Fée Méthane Natacha Lesueur

Graphite mine monotype in printing Fine Art pigment photography Signed, dated and justified on the back 1/3 43x63cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

Jeune Fée Souflée Natacha Lesueur

Graphite lead monotype in Fine Art photographic pigment print Signed, dated and justified on verso 1/3 PA 40 x 50 cm and 55 x 37 cm

This work has been exhibited in the following exhibitions: Las Novias de Frankenstein

Related exhibitions

This Fucking Name Christto & Andrew,Andrew Roberts,Aggtelek,Diego del Pozo Barriuso,Fito Conesa,Momu & No Es,Natacha Lesueur,Ovidi Benet,Pablo Durango

From March 11 to June 30, 2022