I'm the guide inside your sneakers

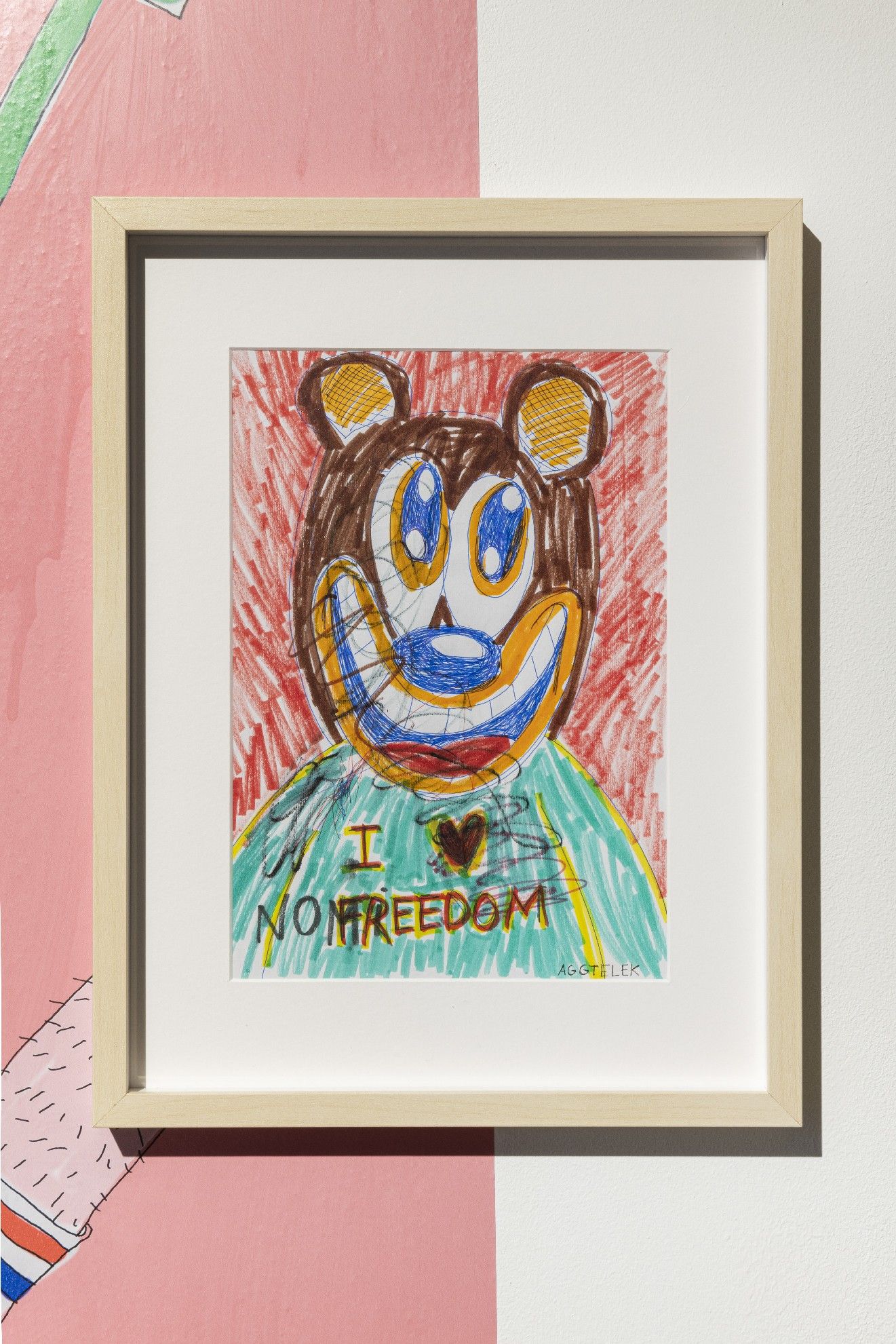

Tokyo, in the nineties of the twentieth century. Kaikai and Kiki, a pair of little characters, nowadays famous in every corner of the capitalized world, were born from the convulsively colonized head of the also famous Takashi Murakami. Kaikai is a namby-pamby boy disguised as a white rabbit who hints at a shy smile and addresses the audience with a complacent look. Kiki, crazier, is always dressed in pink, has three eyes and laughs showing his two fangs. These two individuals appear mostly together, surrounded by a psychedelic orchard of colorful daisies that also crack up with laughter. Too much laughter for a post-postatomic Japan that still resented the inferiority complex and the feeling of frustration experienced after the defeat in World War II! But what Murakami wanted was to project an original, modern and smiling image, flat and infantile, but with a high symbolic/ethical content, of a country that had been a victim but also an executioner. However, the Japanese artist did so, aesthetically speaking, by stepping into the shoes of the "repulsive" Walt Disney: his American conqueror. Over the years, Kaikai, Kiki and the happy daisies put name and image to a business emporium (Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd) that manufactures and commercializes artistic products in series and is willing to colonize the whole planet making of its cute-merchandise a world image. Kawaii (understood as this apparently cute answer from the East to the aesthetics imposed by the West) meant, in the beginning, a kind of bastion of resistance. Today, it has become a product-fetish of the coolest business, leaving the icon/object completely empty. Completely empty? Be that as it may, the strategy had already worked decades before in the United States and in Europe: cultural expansion strategy or pure show business? Doubts aside, the best way to keep the reflection active is to hack in a blatant manner. This is our theme. However, hacking does not mean manipulating in order to massacre, but using and nurturing given realities to provoke new tensions that generate other lines of thought. Perhaps also, to reveal all the latent critical breeching, latent in these works, that the logics of the market seem to want to hide. House of Chappaz BASEMENT, invites Aggtelek Duo (Gema Perales, Barcelona, 1982 and Xandro Vallés, Barcelona, 1978) to shoot point-blank. This pair of creators, with their grotesque and tender characters, between the Western underground and the infantilization of the latest Asian art, caricature the forces of production of the current imaginary, both Western and Eastern, to aim without hesitation at the political subjectivation of the viewer. Parody, humor, conceptual sarcasm and displays of creative freedom function as stings to stimulate social sensibility, to imagine different ethical models and to challenge the certainties held by the instituted order. The bestiary displayed in this exhibition is a direct product of the cultural mix that we have been consuming for longer than we can remember. Aggtelek empathize, they feel part of the gear that produces this supposed aesthetic cooling and take advantage of it to hack it and recharge it with subversive drive. To achieve this, they use the combat weaponry of the art of quick turnover and immediate message. They resort to claims, slogans and other leaflet-like phrases inflated with a positivism of hedonistic tendency (Save Your Head, Make Love, Follow Your Sun, All We Need Is Love, Be Happy...) inspired by the great gurus of New Age rhetoric and psychological revolution. The drawings (with an imprecise and amateur air), which represent iconic motifs of popular culture with a childish touch, (universal flowers of almost mechanical execution on which they stamp little smiles with a whiff of Murakami, cute and good teddy bears, pink kittens, puppies, bunnies...), are also loaded to the teeth with dissident shrapnel: Don't Trust Humans, Fuck The Rules, Fuck The System or the forceful Don't Obey on Pinky's T-shirt, the pink kitty-girl who materializes for the occasion as an art toy. All these elements, despite the sting they cause to the paladins of technique and the guarantors of the "good-doing" by definition, also require creative operations and reflective processes with a highly expressive and critical will. That is to say, they have the capacity to stir the nature of sensibilities, to question the spirit of the times and to provoke ontological perturbation at the first glance. Or do they? Text by Juan Llano Critic and independent curator

Related exhibitions

This Fucking Name Christto & Andrew,Andrew Roberts,Aggtelek,Diego del Pozo Barriuso,Fito Conesa,Momu & No Es,Natacha Lesueur,Ovidi Benet,Pablo Durango

From March 11 to June 30, 2022