Contact / Together Again

If You're reading this... Discontinuities during a crisis of representation

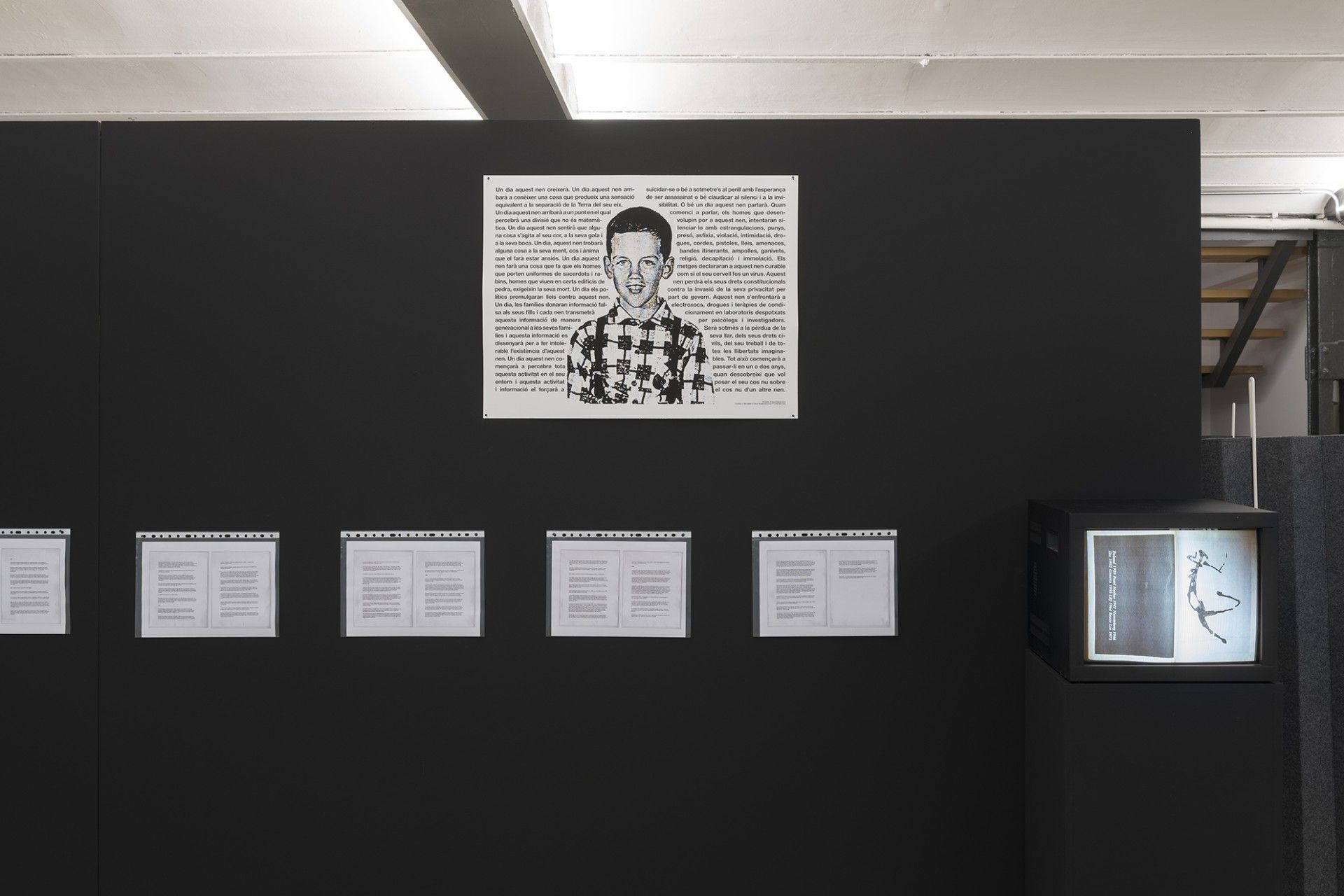

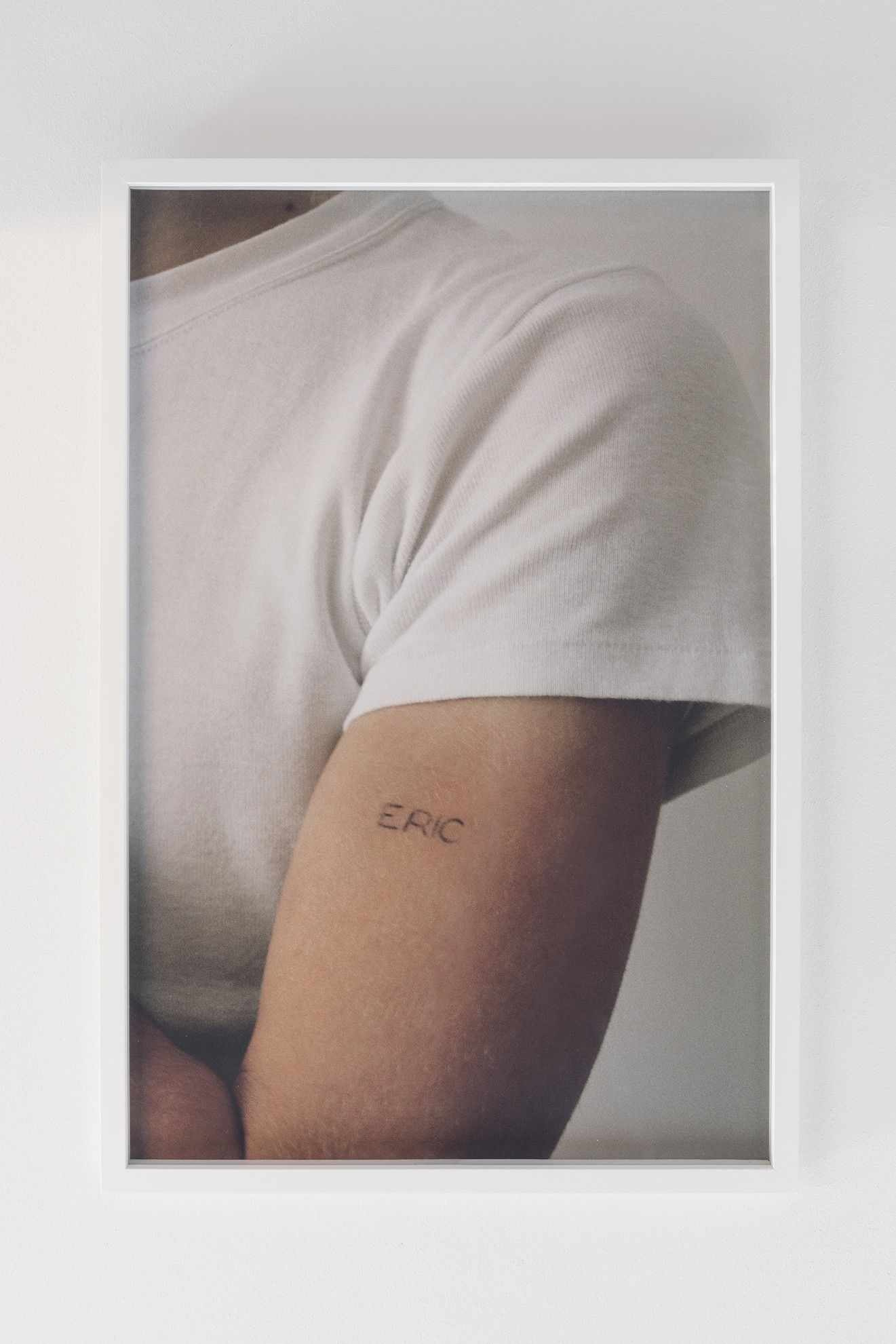

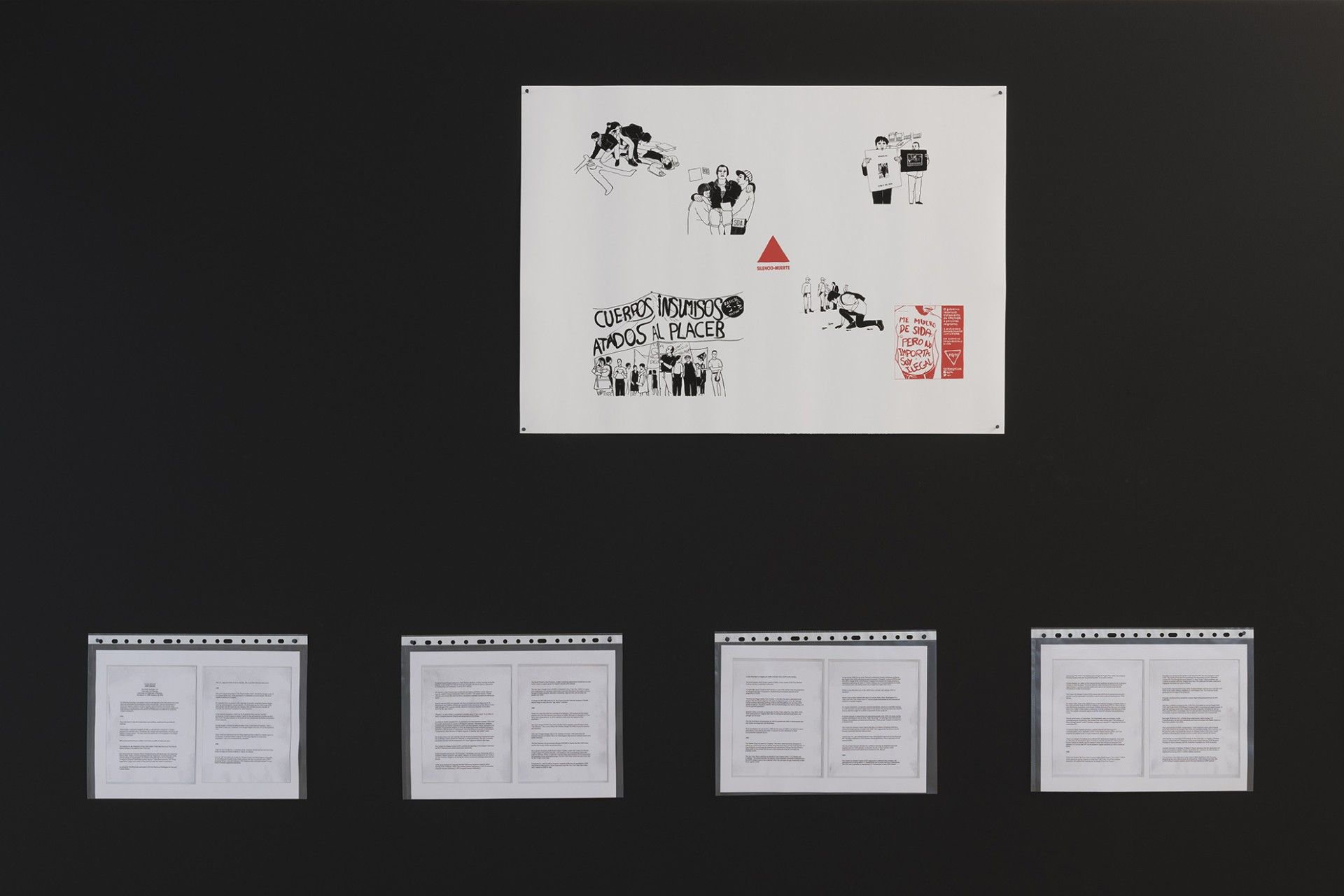

We live in a society in which we have been taught that danger always lives outside of us, hell is located in otherness and the true meaning of cannibal, as Alberto Cardín pointed out in Dialectics and Cannibalism, is, in reality, neighbor. Cultural changes have led to a greater or lesser distance from otherness. For example, for decades we lived under the illusion that the danger would come from outer space, something alien and distant that simultaneously frightened us and yearned for us. In this way, during the period known in the West as the Cold War, this illusion of extraterrestrial invasion and contact coexisted with another much closer and apparently innocuous threat, language adopting the figure of a virus. Although their coexistence may not have been exclusive. "The basic nova technique is very simple: Always create as many insoluble conflicts as possible and always aggravate existing conflicts—This is done by dumping on the same planet life forms with incompatible conditions of existence—There is of course nothing "wrong" about any given life form since "wrong" only has reference to conflicts with other life forms—“ William S. Burroughs, The Ticket That Exploded, 1962 "I think he's in some kind of pain I think it's a pain cry." And I said: "Pain cry? Then language is a virus.” Laurie ANDERSON, Language is a Virus (From Other Space), 1986 Words are dangerous, they shape our way of seeing ourselves and understanding what surrounds us, but names, those are lethal and are inscribed on our bodies. The name of the god Ra, given by his father and his mother, was hidden in his body since his birth, by revealing it to Isis, she becomes all-powerful. Leaving our names at the mercy of other people makes us vulnerable, letting their words infiltrate us reconfigures us, bringing us closer to the idea that others have of us. These are some of the revelations that became evident again as a result of the appearance of HIV. If I use a term so linked to the sacred as a revelation, I do so from the certainty that the taboo is what legitimizes aggression. By assimilating it and renegotiating with it, incorporating new words in order to make ourselves intelligible, what we provoke is a new perception of our reality that we try to tame. Julia Kristeva, who recounts the myth of Ra's name in Le Langage, cet inconnu (1969), also notes that in "certain tribes in western Victoria, taboos demand that the man and woman speak to each other in their language at the same time." once they understand each other's and can only marry a person of a different language." Approaching, maybe learning to love, from the ignorance of the codes and the will to learn them. Perhaps due to this need for translation, she originally signed this work as Julia JOYAUX. Another ceremonial, like the one proposed by Juan Hidalgo in a Milanese autumn of 1974: “TO GET TWO BODIES USED TO LOVE EACH OTHER (…) standing, one body facing the other. in the room (nearby) a large bed and gloom.” Proximity and anticipation prior to contact. “Understand-moi il me faut à tout prix Rejoindre mon amour dans la galaxie Contact” Serge GAINSBOURG, Contact, 1968 The meeting of two realities, the collision of bodies, cultures and identities, at what point does it stop being an act of love and become an alarm? The kisses, the pressure of one skin against another, discovering through other senses, haptic, olfactory or even gustatory knowledge -Douglas Crimp lamented the generations that did not know the taste of semen-. The apprehension may have shifted, our experience of “the AIDS epidemic” has changed, although it has resonated again with the emergence of “the COVID pandemic”. It is curious how we assume hierarchies and gender, who decided to differentiate the gender of two diseases, how the scope of both viruses was determined, according to the denomination that has been transmitted to us, HIV was "restricted to one country" according to the definition that the RAE brings us from an epidemic. It may be that the borders of that nation are not geographical or that HIV was a virus that, according to the etymology of a pandemic, did not affect “all the people”. It is also possible that the blame falls again on History, on its folds and exclusions. "So what's your story, kid?" Matthew LOPEZ, The Inheritance, 2018 BASEMENT (Barcelona) “Overhere! Can't you see where memories are kept bright?“ KATE BUSH, THE NINTH WAVE, 1985 On May 18, 1981, a gay newspaper, The New York Native, published the first story about what the following year would be called HIV/AIDS. We have heard this story, which obviates the appearance of the first human cases on the African continent more than two decades earlier, yet we persist in affirming, in the West, a forty-year coexistence with this health crisis that has transformed social and affective, pointing to some groups of the population as guilty while making other groups invisible. We have seen and experienced changes and evolutions in the ways of addressing the issue and, apparently, we have the distance to rewrite history. Are there ways to manage this traumatic inheritance, to forget our learnings and assumptions about HIV? How can we address these policies and poetics from the artistic field? "Carrying is in my memory like the steps I didn't take, like those lines that you don't know where they went but that keep happening one after another in an unpredictable future." Pepe ESPALIU, An action in AIDS, 1993 “Is is my hope, as it was William’s, that identification of some of these terms might contribute “not resolution but perhaps, at times, just that extra edge of consciousness. In a social history in which many crucial meanings have been shaped by a dominant class, and by particular professions operating to a large extent within its terms, the sense of edge is accurate. This is not a neutral review of the meanings.” Jan Zita GROVER, AIDS: Keywords, 1987 The above quotes are taken from two of the first artistic publications dedicated to the HIV crisis: number 6 of ATLANTICA magazine, published by the CAAM in 1994, which had an image of Carrying as its cover, the action carried out by Pepe Espalíu in Madrid two years before and as a back cover a photographic action by Juan Hidalgo, Rosa, mirror and condom, from 1980. In the Anglo-Saxon sphere it was the magazine October, edited by MIT Press in 1987, this number 43 was called AIDS: Cultural Analysis / Cultural Activism. The need to create a glossary located in which to include new terms, such as PWA, redefine others -family, sentence, general population,...- is interesting, although the absence of words that, unfortunately, would be incorporated into the discourse, such as serophobia, is surprising. This attempt to create and adjust language extended to plastic and visual discourses, although the artistic community itself was aware of its inefficiency: “WITH 42,000 DEAD ART IS NOT ENOUGH TAKE COLLECTIVE DIRECT ACTION TO END THE AIDS CRISIS" Great Fury, Art Is Not Enough, 1988 Meanwhile, other groups, such as ACT UP or Group Material, would seek to apply participation systems in reflections, actions and exhibitions on the impact of AIDS. Even the MOMA joined three hundred other institutions and self-suggested spaces to celebrate A Day Without Art on November 30, 1989, the fact that a member of Visual AIDS, Philip Yenawine, was the director of the educational department of this institution facilitated this invasion of a museum that Yenawine himself defined as “apolitical and disinterested”. And these actions continued… “A Space without Art” was even exhibited in 1991, in which the six curatorial departments participated. In front of that space, neutral and empty in its commemoration, another New York museum exhibited the AIDS Timeline project by Group Material, in which works, dates and data coexist generating historiographical spaces in which to create visual and political education. This tension between the impossibility of representing and the search for other modes of mimesis was maintained thanks to wills and commitments to action. In which cultural agents from fields as diverse as Pop would be involved. “Like a virus needs a body As soft tissue feeds on blood Someday I'll find you, the urge is here” BJÖRK / SJON, Virus, 2011 “There are times when I feel you smile upon me, baby I'll never forget” JANET JACKSON, Together Again, 1997 The collectivization of actions and modes of participation changed, like our bodies, or at least the way we perceive them. So the search for a transformation in the social body was logical. The affections and relationships, as well as the need to form communities and generate multiple and polyhedral stories that incorporate the different voices affected and crossed by this revolution. The modes of action and the stories, as Foucault had already anticipated, were crossed by our self-control mechanisms and we allowed the invisibility of the subordination of discourses and fragmentation. While our day without art was assimilated by a day without presence or, at least, a dramatized presence. In this way, the mural All together we can stop AIDS, which Keith Haring made in 1989 in Barcelona, disappeared in the face of more legal social needs such as those that the city exhibited in 1992. So in this course of genealogies and stories, pandemics and mourning, social alarms and pointing, affectivity and contagion, alliances and invisibility, we move, almost guided by the weight of that heritage and the disappearance of many of our experiences as a vulnerable group, which for the rest of the citizenry it means neighbour until they themselves begin to feel the danger. Text by Eduardo García Nieto, Independent curator and educator Photos by Roberto Ruiz

Related exhibitions

Vocativo Fito Conesa

From September 14 to December 22, 2023

Articulations of Desire, Vol. 2 Various Artists

From May 23 to August 8, 2025

Articulations of Desire Various Artists

From June 7 to August 2, 2024

All Rights Reserved Michael Roy

From June 6 to July 28, 2023

This Fucking Name Christto & Andrew,Andrew Roberts,Aggtelek,Diego del Pozo Barriuso,Fito Conesa,Momu & No Es,Natacha Lesueur,Ovidi Benet,Pablo Durango

From March 11 to June 30, 2022

Mixtape Vol1 Christto & Andrew,Carlos Sáez,Antonio Fernández Alvira,Antoine et Manuel,Andrew Roberts,Aggtelek,Diego del Pozo Barriuso,Fito Conesa,Michael Roy,Mit Borrás,Momu & No Es,Natacha Lesueur,Ovidi Benet,Vicky Uslé,Octavi Serra,Sarah & Charles,Carmen Ortíz Blanco,Pablo Durango

From September 15 to November 25, 2022

Oído Odio Diego del Pozo Barriuso

From April 12 to June 14, 2024

Oído Odio Diego del Pozo Barriuso

From September 23 to November 25, 2022

Artist fairs

ARCO Madrid 2022 Fito Conesa,Michael Roy,Natacha Lesueur,Carmen Ortíz Blanco

From February 23 to March 27, 2022

ARCO Madrid 2024 Antonio Fernández Alvira,Fito Conesa,Maurice Meewisse

From March 6 to March 10, 2024

LOOP ART FAIR Barcelona 2023 Fito Conesa

From November 19 to November 21, 2023